"Let's go to Vichy," my wife Claude was saying, for about the 50th

time. "I can't understand why you have never been. Do you know how far

it is from our home?"

"Maybe 57 miles?" I said.

"Only 95 kilometers," she said. "When are you going to start

thinking in kilometers?"

"Oh, probably when I'm 95."

"You have visited most other places in France. Why not Vichy? It is world

famous."

Odd, isn't it, how you can live with a person for such a long time and remain

unable to confide a simple truth? I didn't want to go to Vichy because I hated

the very idea of Vichy. Not Vichy the world-famous spa--I mean Pétain's

Vichy, Laval's Vichy. The Vichy of 6500 Jews shipped to their deaths by the

French collaborationists who lived in luxury at the Hotel du Parc, surrounded

by brothels, while the rest of their countrymen suffered under the Nazi jackboot.

Of course this had nothing to do with Claude. Her family had fought honorably

during the war, her father had escaped from a German prison camp.Still, she

was French and as an American I found it difficult to express to her how I really

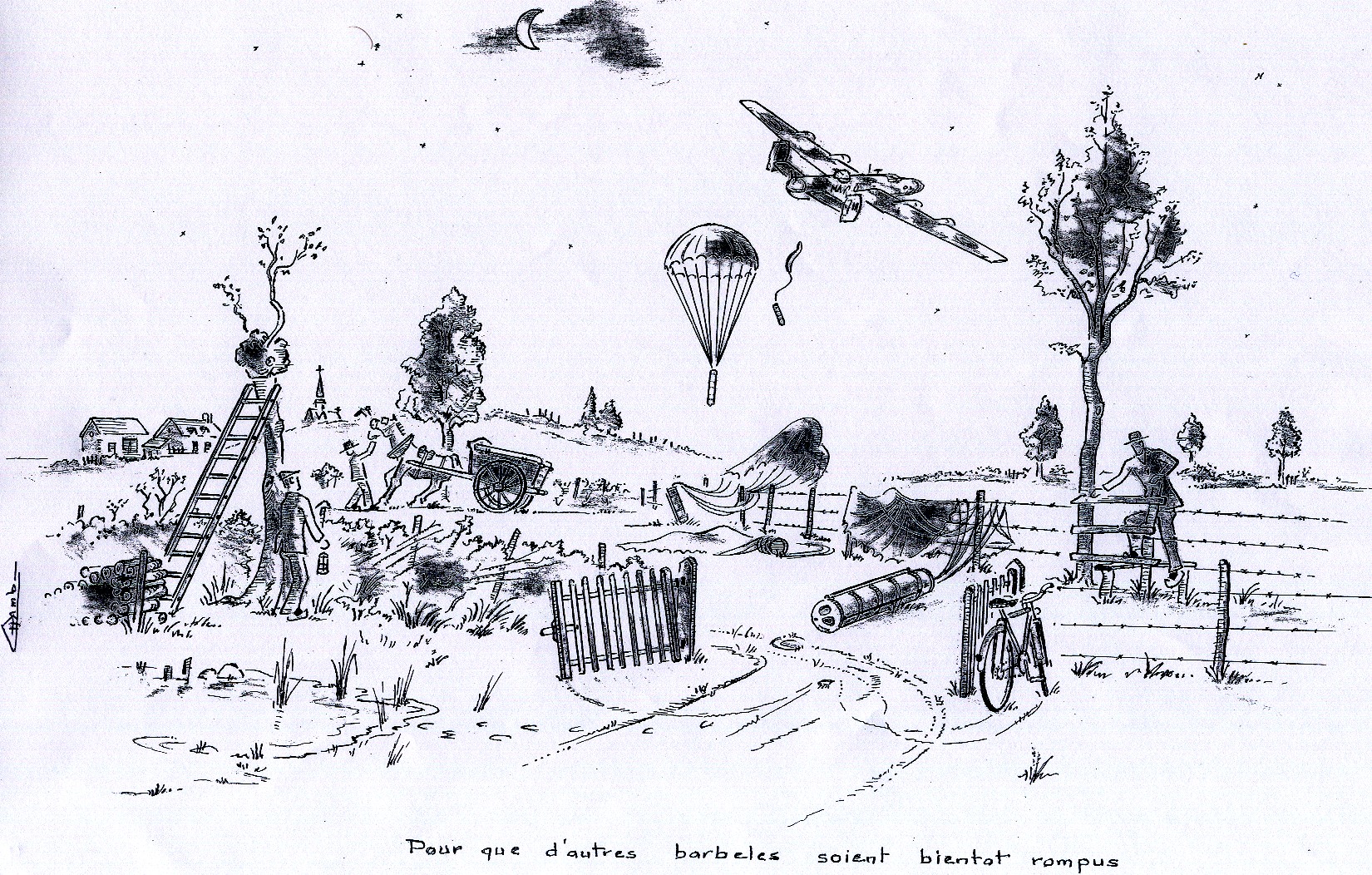

felt. [Below: Local artist's rendering of July 22, 1943.]

Then one day Claude came home and said, "They are having a ceremony to

honor a Canadian aviator who was shot down during World War Two, and the village

mayor wants you to serve as a translator for his relatives who are coming from

Canada and the United States."

"Where was he shot down?" I asked.

"Saint Sauvier."

"That's only about seven miles from here," I said, my interest growing.

"Twelve kilometers," Claude said. "Kilometers!"

"What was he doing?"

"He was flying for the Royal Air Force from London, making a parachute

drop of weapons and supplies for the French Resistance in Saint Sauvier."

By this point I was ready to march out the door to Saint Sauvier. But what

Claude said next made me almost jump for joy.

"C'est arrivé le vingt deux juillet mille neuf cent quarante trois."

I was later talking with my friend, Marie-Thérèse Théveniot,

from Orléans, and I said, "Marie-Thérèse, it happened

on July 22, 1943. Do you know how that makes me feel?"

She said, "Yes, I know. I feel the same way."

Here was the key for both of us: It happened before D-Day, June 6, 1944.

It's difficult to calibrate the role of the French Resistance in the

final years of the war. Certainly there were great acts of heroism before

D-Day.

But if you've spent much time talking to the French, you sometimes get

the impression that everybody in the country claims to be a résistant before June 6, 1944. So, as Marie-Thérèse and I knew,

the date of the Saint Sauvier operation alone meant that it is was a true

example of courage under the most dangerous conditions--the French at

their best.

Making the story even better, Claude's relatives were from Saint Sauvier

and the operation took place just a few, um, kilometers from our

home. I set out to learn what had happened.

Louis Max Lavallee, 23, had been decorated five times and was on his 42nd mission.

His father, a French-Canadian, had met his mother during World War One. Ninette,

as she was called, was a young student who served as a translator for Canadian

troops. She was born and brought up in Auvergne, in a village not far from Saint

Sauvier!

The operation was code-named WRANGEL. Members of the Resistance in Saint Sauvier

chose a field for the parachute drop, marked it with a cross on a Michelin map,

and transmitted the coordinates to London. A clandestine message arrived telling

them to listen to the BBC. When they heard the news-reader at Bush House say,

"The King loves the shepherdess," it would mean the drop was scheduled

for the next night.

The Resistance fighters included seven French, one Italian and one Spaniard.

Aboard the four-motored Halifax flying from London were five British and three

Canadians. They carried two tons of arms and munitions.

The drop was scheduled for 1:10 a.m. A summer storm had blown up, with heavy

winds, roiling the clouds. The plane circled but could not spot the signal light.

Two times the navigator directed the Halifax to the Loire at Blois, to use the

river as a landmark to calculate again the route to Saint Sauvier. At 3:10 a.m.

it started raining. The mission looked hopeless. But one more attempt was made,

and this time the light was spotted--two long, three short blinks.

The airplane descended and the supply containers were pushed out. When the

plane tried to pull up the far left engine failed. It veered to the left and

hit a tree or an electric line, nobody was sure. The noise of the crash awoke

the surrounding villages. The Germans were headquartered not far away. The Resistance

fighters rushed to the airplane and pulled the crew out. They helped five of

them escape. Two were seriously wounded and after medical treatment were imprisoned

by the Germans. Only Max Lavallee was killed.

German soldiers took Max Lavallee's body to the hospital of a nearby city.

His coffin was draped with a British flag. To their credit, the Germans decided

to give him a funeral with military honors. But they intended to keep the time

and place secret. Someone at the hospital alerted the Resistance, and a crowd

gathered along the route, singing the French national anthem. The Germans fired

into the air. The crowd scattered. But when the burial was over and the Germans

had left, they gathered once again to sing the Marseillaise and to give

the Canadian aviator a proper eulogy.

Louis Max Lavallee had written in his journal how marvelous it was to see French

villages, to "share" even for a short moment the lives and hopes of

the people. And the French villagers were determined not to forget him. Shortly

after the war, in July 1945, the people of Saint Sauvier erected a stele to

his memory. Journalists, both in France and Canada, took up the cause, and in

1952 he was reburied with honors in Canada.

Now Saint Sauvier was going to name the most important place of the village

in his honor. His sister and brother and other relatives would come from Toronto.

The British RAF and Canada's military would be represented.

"Great story!" I said to Claude. "Tell the mayor I'll do anything

to help. This is really going to be a wonderful ceremony."

Claude works with a charitable group that is restoring a 17th century chapel

near Saint Sauvier. They decided to have their annual fundraising lunch on the

same day as the ceremony, adding the touch of food and drink, a requisite for

any important French occasion. Claude began to give me weekly bulletins on the

planning.

Thomas Jefferson said he liked everything about France, except the weather.

Being a Southerner myself, I understood exactly what he meant. To look at weather

reports on Paris TV is usually a trying experience. The weather people stand

before the map and every one of them--both men and women--rub their hands together

unctuously as they give the météo. Quite often the operative

word they use is "Variable"--which, translated into simple

English, means they are clueless, variable can be sunshine or rain.

The summer had been very variable, chilly and rainy even in August.

But as we moved into autumn, the weather began to change spectacularly--sun,

sun, and more sun. Perfect for the memorial ceremony.

The dedication of the Place Louis Max Lavallee in Saint Sauvier--September

23, 2001. It was sunny the day before and the day after. |

There was a big crowd, a military honor guard, a band, high-ranking officials,

flags galore--and umbrellas. As we gathered many people were cheerfully optimistic:"The

rain will soon stop," they said, peering at the sky. Nah, I knew better,

it was coming out of the southwest from the Atlantic, we would have a day of

it.

Where was Claude? We were supposed to be the translators and the ceremony was

about to start. I certainly wasn't going to try to do both versions by myself

at such an important occasion. Claude was constantly warning me about using

the slang I picked up from my guy friends. Would I make a mistake and call Max

Lavallee a mec?

I began to search desperately among the sea of umbrellas for Claude, peeking

under each one. Practically everybody knew her but nobody had seen her. I finally

ran into Suzanne Pierre, our next-door neighbor.

"She has gone to change her shoes," Suzanne said.

"She's what?"

"Claude rushed out of your house this morning and discovered when she

got here that she was wearing a brown shoe and a black shoe, different styles.

So she has gone to borrow a proper pair from a friend she knows in the village."

"Who cares!" I said, exasperated.

The men around us laughed. Even Suzanne smiled. If you are a woman, just ask

your guy what color shoes you were wearing yesterday. Men see but don't notice.

She could have been wearing a tennis shoe on one foot and a stiletto heel on

the other, and guys wouldn't have taken note. Well, maybe a shoe with stiletto

heels, that would register. As I knew, though, she would be worried about what

the women thought--as if anybody would be looking at what anybody was wearing

in this rain!

People were taking their places. Max's brother John, from Seattle, and Colette

Anderson, Max's sister, and her daughter Jeri, from Toronto, were in the front

rank. In theory, I was supposed to be with them as their translator, but I hadn't

even introduced myself as I searched for Claude.

Max Lavallee's relatives at the Saint Sauvier ceremony. |

|

Claude talking to Max's brother. |

It turned out not to matter. This was no day for an elaborate translation.

The rain had changed that. Besides, Max's sister spoke French and her daughter

Jeri was cool enough to know that one flowery speech sounds like another. Sometimes

it is better not to understand and let your imagination take over, to edit out

the inevitable clichés.

In fact, the speeches became a bit of a problem. Brevity is not the soul of

wit in France, nor in any Latin country, and no one had taken into account that

it might rain. The mayor ended one speech by walking to the lectern and flipping

the guy's pages to the end, shortening it considerably.

Still, it was a very impressive ceremony. René Chambareau, a local historian,

gave a vivid account of the events on the night of July 22, 1943. (He also did

the sketch I've used in this letter.) The band played the national anthems,

flags were raised, salutes exchanged.

But what I found most impressive was the grace and strength of character shown

by Max Lavallee's relatives. I was busy taking photos, something not easy to

do while balancing an umbrella, which I finally tossed away, so I was getting

soaked and feeling a bit sorry for myself. But I was snapped out of those feelings

by seeing Colette Lavallee Anderson stand in front of the crowd, heedless of

the rain, and give an elegant speech in French, thanking the village for honoring

her brother. This was what World War Two was all about--men and women like the

Lavallees.

Max's sister, Colette, gave a touching and elegant speech, thanking

the village and guests for honoring her brother. Max was the eldest of ten children. Five of them served in World

War Two. |

Before I begin to sound too sentimental, I should add that my friend Henry

from Paris made a reconnaissance to see what the villagers thought about the

ceremony. They told him they found it wonderful and moving, the truth of what

had happened on July 22, 1943.

But a question about that night still lingered in their minds.

"What happened to the money?"

"What money?" Henry asked.

The British always dropped a sizable amount of cash along with the weapons

and munitions when they supplied the Resistance. The money had disappeared during

the chaotic events of that night.

Who got it? They looked at each other suspiciously.

"Eh bien," as the French say, "c'est la guerre." We'll not let that blemish our heroes.

After the ceremony naming the Place, we moved to the Monument aux Morts,

to honor the men who had given their lives in the two world wars and other

conflicts.

Practically every village in France has a monument listing the names

of those killed, and by visiting them one can easily see what a catastrophe

World War One was for the country and understand that the first war goes

a long way to explaining French actions in the second.

On our village monument, the name of one of Claude's relatives is embossed

in gold. He was killed on the last day of World War One.

This completed the official ceremony, and now we were placed in the hands of

Claude's do-gooder group. They had set up a tent outside the Salle des Fêtes--a

recreation hall that most villages have for public events--where apéritifs,

wine and punch, were served.

This would have been a great place to meet and establish rapport with the various

officials from Paris and the local government, if weather conditions had been

different. As it was, we huddled together for a quick drink and then quickly

moved inside, to the Salle des Fêtes.

Claude's bénévole group includes seven or eight excellent

cooks out of the 160 members. They get together and split up the cooking chores

for the various dishes. What they serve is always outstanding. But to my puzzlement

they also insist on serving the guests themselves. This slows down the appearance

of the different courses considerably. Nobody has jumped at my suggestion that

they recruit waiters from a ready group of volunteers, to speed up things. Claude

says they all consider themselves equal, as both cooks and servers.

| |

After the ceremonies, we huddled under the tent for a quick

apéritif. And then rushed to the dry and warm Salle des Fêtes. |

Claude's charity group includes excellent cooks who insist

on doing the serving themselves. Claude (left) serving Max Lavallee's relatives. |

Once everyone was installed at tables in the Salle des Fétes,

the occasion turned very festive. The menu consisted of six courses. After

the first three, a trou normand would be served as a break in the

meal--green-apple sorbet, with a small glass of plum brandy, from the

mayor's cellar.

I knew there would be dancing later on, so I set the trou normand as my departure time. I wasn't feeling well, after being soaked to the

skin.

I had my photo snapped with Max Lavallee's sister, Colette and her daughter

Jeri (right) during the break before I left. They were made of tough stuff,

and didn't seem at all bothered by the day's weather.

I caught a cold that I couldn't shake for three weeks.

VISITING VICHY

German soldiers making their victory march down the Champs-Elysées

in June 1940. |

After brooding about the Saint Sauvier ceremony for a few weeks, I said to

Claude one morning at tea: "I'm ready to go to Vichy."

She said, "We should spend two days."

"Two days? Why? It's only 57 miles from here. I mean 95 kilometers."

"We need time to see where people take the waters. Vichy is the world's

preeminent spa."

"I don't want to see the spa. I only want to see the Hotel du Parc. I

want to see the place where French collaborationists worked and lived and played."

"You'll be missing something important."

"Well, I'll miss it this time. Maybe we can return later."

Marshal Pétain leaving the church at Vichy for the Monument aux

Morts--July 14, 1940. Pierre Laval (right, black coat), Vichy's prime minister,

was shot after the war. |

On June 6, 1940, with the Germans advancing, France's prime minister

Paul Reynaud made a radio speech to the nation.

"More than ever before," he said, "we have confidence

in our armed forces."

Four days later the government fled Paris like scared rabbits, first

running south to Bordeaux and then to Vichy, in the center of the country,

after signing a truce with the Germans and becoming their collaborators.

According to official history, they chose Vichy because, as the thermal

capital of Europe, it had plenty of hotels and good telephone connections.

The hotels were requisitioned, and Vichy became the shelter for the French

government until August 1944, when my father was fighting his way with

other American troops, right up the center.

Marshal Philippe Pétain, a widely-respected World War One hero, became

head of the collaborationist government at Vichy, while a little-known brigadier

general, Charles de Gaulle, appointed himself as head of the Free French in

London. The French who were embarrassed by Pétain's role unfailingly

pointed to his age--84--and suggested that he was gaga. There was no ameliorating

explanation for Pierre Laval, so they shot him by firing squad after the war.

His last words were"Vive la France." The question was, which France--Vichy

France or Free France? Charles de Gaulle, the new French leader, tried to sweep

that era under the carpet of history as quickly as possible.

In any case, I didn't intend to get submerged in historical details. I just

wanted to see where it had all taken place. I drove into Vichy across the Allier

River and followed the signs to the tourist office. I rather stormed into the

office, shoulders hunched, assuming the role of the American journalist who

shall not be denied the truth.

I was greeted by Françoise Gioux, an attractive blonde in her mid-thirties

who spoke excellent English.

"Can you tell me where the Hotel du Parc is?" I said. "You know

what I am talking about, right?"

"Yes," Françoise said, calmly.

"Then where is it?"

"It's right here," she said.

"Where?" I asked, confused.

I looked around the spacious, modern office. I saw no signs of lurking collaborationists.

To my surprise I discovered that the Hotel du Parc, headquarters of

the Vichy government, is no longer a hotel.

Françoise Gioux is the blonde in the middle of photo. |

|

"The Hotel du Parc was renovated and turned into private apartments in

the 1960s," Françoise said. "The mayor and the people of Vichy

wanted to remove this unwanted symbol. The hotel's restaurant became the tourist

office. You are standing where they probably washed the dishes."

"Do you get many guys like me?" I asked.

"Like you? No. Oh, you mean journalists? Yes, we get quite a few. But

we also see regular tourists who are interested in the Vichy era. They are often

shy about it. They will ask a few questions, and then come back later and ask

some more. These are mainly foreign tourists, American, British. Sometimes we

get aging French tourists who are nostalgic for the Vichy era."

So this was it? I don't know what I expected to achieve by my visit. If it

was some sort of exorcism, it didn't occur. One thing I knew--between Vichy

and Saint Sauvier, there was no contest. I was ready to go home.

I stopped across the street from the tourist office to have my photo

snapped with the Hotel du Parc in the background, standing by the monument

to the 6500 Jews shipped to their deaths by the Vichy government.

The monument had been placed only four months earlier, and had already

been destroyed by vandals once.

On the drive home we encountered heavy rain and fog so thick we could

hardly see. I missed the turnoff from the autoroute and had to circle

back.

When we pulled up at the house, Claude said, "I bet you are glad

to be home." She was talking about the hard drive. But I was thinking

about something else when I replied.

"Yes, I really am," I said.

Recipe Eight

Charlotte Saint Sauvier

"I think I'll run one of your old recipes from Spain with this Letter,"

I told Claude.

"No," she said. "I made the dessert for the lunch at the Saint

Sauvier ceremony. Why don't you do that? It was a Charlotte, and everybody liked

it. We can call it 'Charlotte Saint Sauvier.'"

"Well, I've already got the Letter written and I want to put it on the

site as soon as possible. How long will it take you to do it?"

"Oh I can write it five minutes," she said.

Yeah, sure. I gave her a day and then asked again.

"The recipe is simple to make, but complicated to write," she said.

"Besides, I am a little nervous right now because I'm making, for the first

time, a clafoutis of broccoli and and smoked salmon for the New Year's lunch."

Claude working in the kitchen. There is flour in her hair, flour on her shirt. She is a hands-on cook. |

"I don't think a cook should try out something she is making for

the first time on her guests," I said.

"Annie told me how to make it."

"Annie's not here."

"Don't bother me. I'll do the recipe after lunch."

That set me to thinking. Unless you are just recycling a recipe from a cookbook,

writing one is not as easy as it might seem to those who have never done it.

Especially if you are translating from French into English. There is an element

to all good cooking which is an almost indefinable art. Putting it into words,

getting the brush strokes of art right, is often difficult.

Claude was working on the recipe at a table by the fireplace, long after

sundown, a paperback copy of Julia Child in one hand to try to find the

proper terms in English.

Below, some of her notes. The sentence next to the illustration reads: The chocolat should run on the sides with irrégularités.

So without doing much editing of her original notes, here is what she

came up with.

What you need

1. For the nut cream:

170 grams (6 oz.) of butter

150 grams (5 1/2 oz.) of sugar

100 grams (3 1/2 oz.) of chopped walnuts

1 cup of French custard sauce + 2 Tsp

(The custard sauce should be thick)

2. For the topping:

100 grams (3 1/2 oz.) of chocolate

40 grams (1 1/2 oz.) of butter

Some walnut halves for decoration

3. A cylindrical mold

4 inches high, 7 inches in diameter

Line the bottom of mold with waxed paper

4. Mixture of water and alcohol

Use water and rum or orange type liqueur

(Grand Marnier). You can substitute orange juice

Ratio: 2/3 water, 1/3 alcohol, for one cup

5. About 24 ladyfingers, to be purchased

Cream the butter and the sugar for a few minutes. It should become pale yellow

and fluffy. Now beat in the nuts gently. Finally add the custard sauce. Keep

at room temperature.

Quickly dip the ladyfingers one by one into the water and alcohol mixture.

Then place them upright around the side of the mold, ensuring that their curved

side is facing the mold and that they are closely pressed together. Finally

line the bottom of the mold with ladyfingers.

Pour the nut cream into the mold, banging the mold gently on the table, to

ensure that the mixture is evenly spread throughout. When it is full of nut

cream, finish by laying ladyfingers at the top to seal in the mixture. Snip

off any protruding ladyfingers, making it level at the top.Cover the mold with

waxed paper and place a saucer of the same dimension on top. Put it in the freezer

for an hour and afterwards keep it in the refrigerator overnight.

The next day, remove the waxed paper from the top. Turn a serving dish upside

down over the mold. Reverse the two so the mold is on top of the dish. Tap gently

while lifting up, so the Charlotte will drop into the dish.

Prepare the topping by putting the broken chocolate in a sauce pan. Then put

the sauce pan into a larger sauce pan half-filled with water and slowly bring

to a boil to melt the chocolate. Remove and add the butter. Mix well. Pour it

over the charlotte. The top should be covered but the chocolate should drip

unevenly down the sides. (This is not an icing.) Decorate with the half walnuts.

Put it into the refrigerator until you are ready to serve.

[Oh, by the way, Claude's first-time clafoutis of broccoli and smoked salmon

drew raves at the New Year's lunch. When I suggested that it was risky business

to serve guests something a cook had never made before, every woman at the table

disagreed with me. So what do I know?--ZG] |